KNOCK DOWN! And then?

Voices from the Crisis, Voices against the Crisis – 06

English translation by Alexandra Hudson

(Text in German: here)

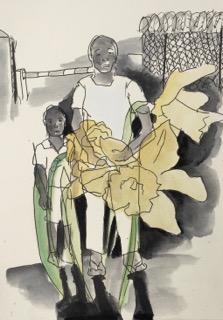

What do the omnipresent media imagesof this crisis call forth? How do they affect our perception and behaviour, now, as well as in the future? How are emotions translated into speech, what are the consequences for private and political action? And what does freedom mean in this context? Barbara Philipp has created a graphic Knock Down diary – some pictures can be seen here, the captions are the artist’s own notes. In a multimedia exchange with Evelyn Schalk, she speaks about the very personal balancing act between artistic reflection, political analysis, lived-out multilingualism, the struggle around gender roles and touching our way towards a reality, which hasn’t yet become real.

TATsachen: Since the start of the Corona crisis you have documented your experience of this exceptional period in the form of a graphic diary. When I look today at your drawings of this week, it is like a journey through the media images and front pages, inseparably entwined with personal references, emotional reflections and very precise observations of individual details and how they fit into the wider whole. What impulse propelled you to begin to draw and how has your recourse to this changed over time?

Barbara Philipp: Shortly before the outbreak of Corona my father was taken to hospital in Graz. 24-hour intensive care was briefly discussed and this type of treatment would have been recommended for him had his condition not rapidly deteriorated. My family and I could say goodbye to him and on 14 March we left Austria for the Netherlands.

That was still quasi the old world. The first regulations appeared shortly before the funeral. Total Lockdown in Austria came two days later. I travelled to a country, where an “intelligent Lockdown” was imposed. Every day and every decision in this first period counted, because shortly after it would not be possible to be take them freely and individually.

My family life in different countries catapulted me directly into the continuously changing responses to the Corona pandemic. That is why I started to draw. To understand, to record and to reflect.

Suddenly we were hit by…

… the virus invasion …

…the pangolin in us lurks everywhere …

The first impulse was the question of the origin of the virus. The pangolin, which we only know here from schoolbooks, gave flight to my fantasy. We read media reports, snap up headlines. What do we do with these? How do we process this information? And above all, what sticks with us? My children heard of bats as the transmitter and suddenly this hearsay is amplifying traditional fears, stoked by the famous vampire stories.

The carer who has her family at home, her children are cared for by her parents because of her work.

Politically devalued, suddenly they have become “key workers”. What would happen if they all went on strike?

The 24-hour care service in Austria for example, which is principally staffed by mostly female carers from Eastern Europe, has been on the brink of collapse for weeks. These workers were eagerly viewed as exploitingthe “Welfare State of Austria” and cuts to their family support were accepted by society. And suddenly in one stroke the current situation has exposed the sanctimonious aspect of this populist move: because without help from outside the so-called “Social state of Austria”: in terms of health care for the elderly, crumbles to the floor! Now who has exploited whom? Already here was something which wasn’t functioning at all before. My drawings in the first two weeks of bats and pangolins, border closures and care of the elderly connect these thoughts, reports, and personal experiences, which are perhaps more easily expressed through images than language.

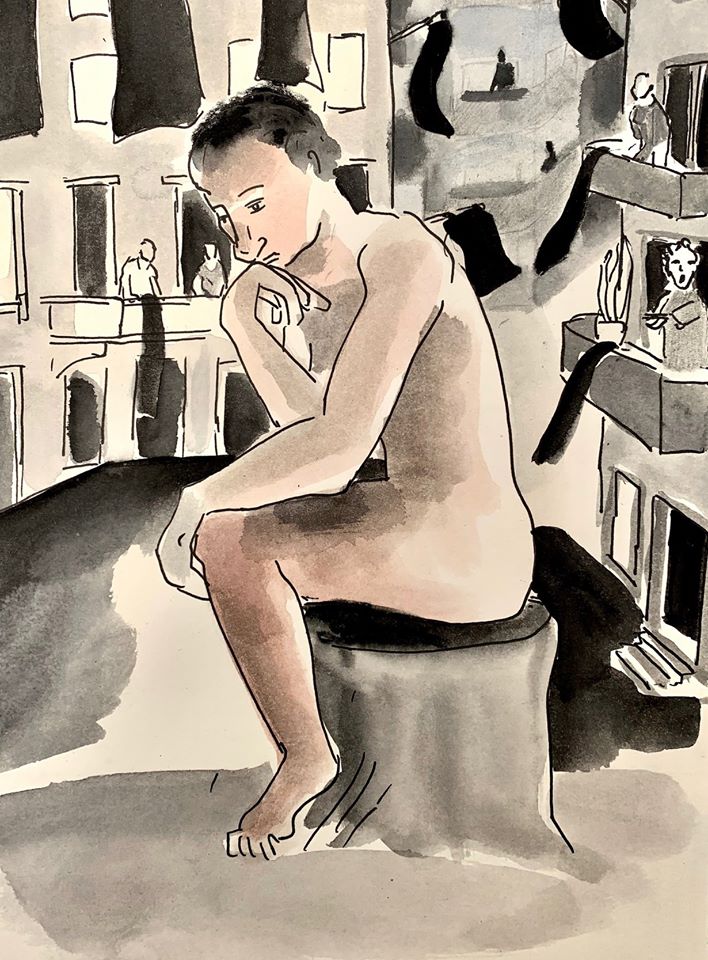

In these weeks, my Austrian-Italian family and I followed events and political decisions in different European countries. At present (week 8) I’m interested in the debate around Schwarzen Löchern (black holes). By this I mean the gaping emptiness in concert halls and theatres, in front of cinema screens, and on our own screens infront of us, which show numerous little black boxes during every conference call, which are supposed to suggest the presence of other participants. A strange feeling. Balconies have also gained in importance in these weeks, balconies and staycations are experienced as the new outside. Balconies were and are still used as a political stage. Here they meet again – the public and the private.

I’m interested in the restrictions of the moment in the private and the politicial. There is not one reality in the Corona age, rather each of us must battle with the terms of the Lockdown and go about this differently. The crisis shows us society’s wounds, which were eagerly overlooked before. I think that my recourse to drawing during these weeks can perhaps be pinned to these verbal exclamations and it changed as slogans like ‘Stay Home’ and ‘Social Distancing’ sparked my artistic interest, but also in that I occasionally used my own terms in relation to developments, as a starting point for drawings, (for example black holes and balconies.)

Balconies…

… a de-

-bate …

The extent of this crisis is perhaps most evident in the linguistic dimension. As you have just mentioned balconies, Peter Weibel said today the word Wohnhafthas only now acquired its actual meaning through Corona.

Wohnhaft, wow, I hadn’t thought about that word yet. I find it very apt.

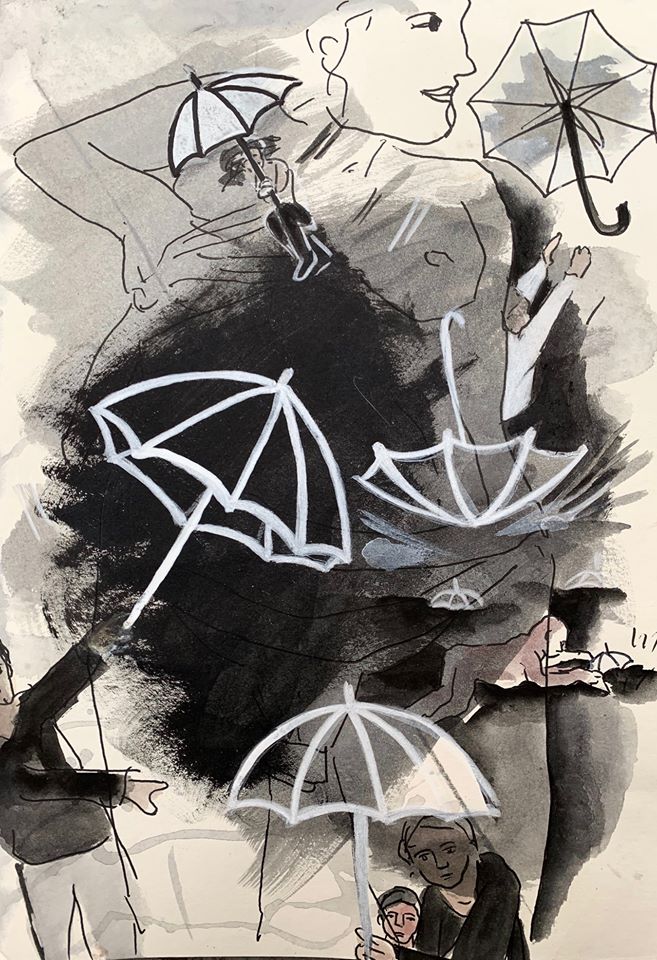

From the very start communication has been almost exclusively through imperatives (Stay Home, Look after yourself, Look out for yourself – look out for me, Keep distant etc.) and following a very militaristic arsenal of words, many politicians (of course Trump, Orban, Vucic, but before that Macron) said literally: We are at war. It is a fight, a battle, medical equipment becomes to some extent war machinery, there are restrictions on going out, border closures, directives, orders.. which are not empty, but rather become bitter reality, yet they hold a surreal emptiness, because this is about an illness and not a war; the war is being made out of it. To what extent is this monumental experience multiplied for you through your multilingual everyday, which allows you to follow developments and, particularly in the media, in many languages and perspectives in parallel?

Yes, experiencing this in different languages gives me images as in a Kaleidoscope which I am looking through, and because I get dizzy sometimes, I try to capture individual images through drawing and in that way make them my own and give them their own order. That is to say to create other Patterns, depending on how one turns the picture.

And that happens with language as well, in particular when you dive into another language and understand the context but perhaps not all the intricacies. But also every known word in another language has for me its own heights and depths, its own resonance and tone of meaning. In language you understand a lot intuitively and then you fly with the form of the sentences, travel with them, when you live with them. Language is a source of inspiration for me and when for example I see Guiseppe Conte and then the Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte speaking, I notice huge differences in how announcements can be made public. Conte speaks about punishments and last week he gave me the feeling as if he were talking as a father to children. Shortly before I’d heard Rutte’s press conference on the radio, which mentioned self-responsibility and advice a lot. He spoke of an “adult society”, I asked myself if these words, in transmitting a feeling of superiority, didn’t actually disguise more than what freedom would allow. These are nuances, codes of behaviour, which with time, one can either understand and decode, or maybe not. I lie somewhere inbetween, a lot appears raw or unfamiliar but this feeling of the unknown also makes me vigilant. I don’t want to accept so rapidly the “general understanding” – with the risk of misinterpretation.

Through misunderstanding, through failure, there is for me however a recognition which brings one closer to the meaning of the word. That interests me. There is not one wisdom or one truth. And so I come back to the image of the kaleidoscope. Drawing sorts this information anew, allows my self to acquire it. As a consequence I can then start dialogue with others.

As you say, the war rhetoric used by some politicians is interesting and also shattering. Isn’t war diametrically opposed to illness?When people are fighting for their lives due to medical reasons, a war is waged ad absurdum. Perhaps we shouldn’t lend our ears to the linguistic warmongering, but rather we should listen to the voices of those who are caring. The German, this intricate word “sich kümmern” – to take care – s´occuper de qn/qc. Here again different worlds and fields of meaning swirl around with it.

Closing the borders to neighbours, solidarity is twisted and used whichever way the state wants: solidarity in national terms but not in European and global thinking – Europe talks about solidarity. For whom? A mask to respect others.

Certainly, it is tempting to reproduce this specialised vocabulary of war jargon and taking care – with both, it is about fearing for your life. But the strategy for creating a solution is not the same. How does a politician loyal to the state speak to their citizens?

I find the closing of borders and thinking in terms of the national state alarming.

I am a convinced European and believe in the idea, the ideal of a united Europe. The fact that Europe is not united in solidarity weakens the many positive tendencies and easily makes room for a mode of speech that splinters Europe. And you can clearly recognise that in the newspaper reports in the different languages and jargons. Unfortunately I don’t speak an Eastern European language, that would certainly be a huge broadening of my perspective.

Verbal Paranoia …

… attacking, spying …

Generational lockdown

Before the crisis I only rarely bought Dutch print media, sometimes the Amsterdam city newspaper Het Parool, to be informed about local events. This has now changed. Although you can still read a little of nrc or die Volkskrant (two of the largest daily Dutch newspapers) online, I have made a habit of buying the weekend editions to be informed about the country in which we live. That is the danger when you have moved somewhere, to remain locked in one’s own language bubble.. I enjoy reading in German, Austria’s Standard newpaper everyday, but also articles from Germany’s FAZ or Switzerland’s Die Zeit newspaper ensure I don’t become detached from my mother tongue. My partner is Italian and together we speak French. That means I hear a lot about the Italian media from him. At the start we often watched the Italian news on television, also because his mother has been stranded with us and hasn’t gone back to Italy since the start of February. Apart from that, television doesn’t really play much of a role with us, but the Internet is all the more important. As we both still have a strong connection to our friends from our student days in Paris, we also wanted to keep informed about the situation in France.

And yes, because Amsterdam is very international and we communicate a lot in English, I also like to read articles in the Guardian or from other newspapers which friends send to me on certain topics.

I see your linguistic and pictorial appropriation in this context, not least as a self-empowerment, as a taking back of the power to define, publicly and personally – is this perhaps where art attains its real meaning?

I can’t give a general answer to the question of the real meaning of art. Art for me is like one’s own language, which one can learn, and the better you understand its vocabulary, the more you can, spiritually moved, free yourself from your shadow and broaden your horizons.

Art blows borders apart – the opposite of what is happening now. Is that perhaps a reason why support for the arts, that is to say emergency funding, is now failing in so many countries?

Furthermore, art would be a language which is not tied to one nation. We are steered by this national thinking, but art is transcendental, it can cut across things and liberate the spirit, (now I have to laugh and think about the saying of the Vienna Secession, Der Zeit ihrer Kunst, der Kunst ihrer Freiheit, To every age its art, to every art its freedom, which still has its relevance, particularly so today.

In one of your notes you mention the “malelanguage”, as the one that forges plans – if I am not mistaken – in the same week as which you take up hooped skirts as the new old idea of Social Distancing in your drawings. Do you think that in this crisis as a result of increased financial pressure, but also as a result of having to stay at home more, and the public presence of power, that old gender roles and modes of behaviour will strengthen further/return? Images transmitted by the media, at least in my opinion, seem very similar internationally… or are processes changing because of an enforced and different situation offering chances for new interpretation and formations?

Slipped through the net, caught by the net, hooped skirts as a new fashion in our heads and in “Social Distancing” on the street (I don’t know anymore what is behind the masquerade. Malelanguage, which forges plans, but deliberately fails to balance things.

That is an interesting question. I have just written a short text for a book presentation in Vienna. I think that the answer to your question already lies in part in this text. Yes, I think that financial pressure in families is forcing women back into a role that “they do better anyway”. That is the view of the herd that often resonates in the press. Women go back to the kitchen! Isn’t that normal in crisis times. It makes me angry. I simply cannot agree with this. Whether female or male, Transgender or Transsexual, I think that every person can help provide. And that one should share these tasks in a family, without one person feeling more responsible than another. Social and economic factors however yank the corset around women tighter. And with unequal pay or a part-time job, which women often have, precisely to have more time at home with the children, the question of who runs the household is obvious. Women still live with the feeling of responsibility for the domestic sphere. They still grow up with this. Patriarchal structures live on inside people’s heads and then become suddenly very evident in emergency circumstances like this one, and difficult to circumvent because of a lack of alternatives. As an artist, the question of earnings and division of labour is naturally even more precarious, because there is seldom a steady income.

I can only hope, that the laying bare of these sore points in society makes politicians more aware, and that they use the opportunity to lay the roots for change. With the climate change movement of the last years some things have taken place, although not enough. It trigged a media maelstrom, but action should now follow. But we need dynamic advocates for climate change and equal rights. The outcry and protest in society must be very strong, for things to be heard and not to peter out – I’m concerned that the voices will be drowned out, because the power of rules, particularly in an exceptional period, can be very appealing, and some states have already used this to depart away from, instead of moving towards democracy. Equal rights then quickly become just an uncomfortable minor issue.

To mention something positive as well though: I am hearing from many friends of mine that spending time at home has brought them closer to their partners, and that they have been doing things together or trying out new things together precisely because they have had the time. Along these lines, we can allow ourselves the luxury of asking – does our economy have to keep growing? What would happen if we, as a society, took more time for ourselves and to consider things, rather than just working?

There is such benefit to be had from this – because then not every step we take each day would be efficiently calculated. There would be time to be creative, and my thoughts are leading me to the idea of an unlimited basic income.

In the preserving jar …

… and outside

In Amsterdam (I can’t speak for the whole country, capital cities are always different) it appears that the burden of childcare is shared more equally by partners – there are the renowned Papa and Mama days of the week, and many fathers only work 4 days a week when their children are young. Same-sex marriages are an everyday part of society and often it seems to me that same-sex partners have an even fairer division of childcare.

However, when you look deeper at society, you see that part-time workers, also in the North, are mostly female, and that only since 2019 has there been a Papa/Partner week after the birth of a child. Since 2020 partners can request 5 weeks off. You wouldn’t think it, but in this respect, Austria offers more choice. Maternity leave is limited to 16 weeks in the Netherlands, after that you must return to work – mostly out of financial necessity, which many women don’t find necessarily a good thing. In this respect, people’s needs receive only minimal consideration.

The comment by Austrian Chancellor Kurz, however, that one shouldn’t be ashamed to send children to childcare if you can’t manage anymore, made me feel very queasy. Precisely because Kurz is not an old man, this antiquated comment alienates me even more. What is it supposed to mean? It surreptitiously suggests that nurseries and childminders are less professional than parents when it comes to education, and therefore that training to become a childminder or infant teacher is held with little regard.

This low regard is felt by many of the key workers who are keeping society going now. It would have been good, if politicians had been clearer earlier, that the salary and benefits in these jobs are completely inadequate.

You can see that more or less across the whole of Europe. An aim we should work for, politically and as a society, is the proper recognition of care, so that women don’t fall into poverty in old age and so that it also becomes an issue for men in their working and private lives.

I have the impression that the current situation is oscillating (given the different conditions and progressions of events) between a new consciousness of the fragility (and unequal distribution) of freedom but also of fear. How free do you feel at present?

That’s funny, I was thinking of precisely this question yesterday in my study. About the volatility, and about what still remains. The fear, the uncertainty, because it is still not normal to go out and drink a coffee. In Amsterdam Cafés and Restaurants aren’t open yet, we are not obliged to wear masks, (this comes into force on June 1 on public transport) but still it seems like we have to wait and see what will come.

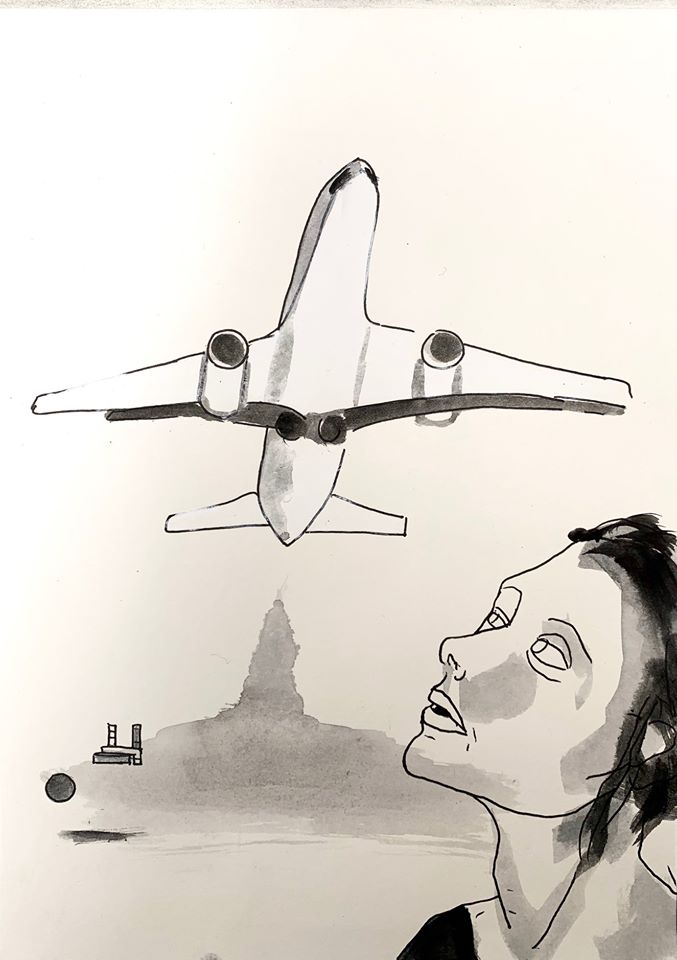

„Please wait!“, we are in an endless queue. And what happens, if you simply want to get out? Getting out would mean, jumping out of an airborne aeroplane. It is just they aren’t flying at the moment. Jumping out of this new reality, I would like to do that a lot. But as there are hardly any “aeroplanes” we have to fall back on ourselves. Everything revolves around being able to maintain our balance. Mastering a balancing act. We have been putting this into practice for two months. A friend told me, that she had to get out of her bubble, and that was in no way easy. If the bubble bursts suddenly, then the impact will probably be painful. That is how I feel at the moment.

Our bubbles are at risk of bursting…

Bailout for essential work

Feeling the borders

And as another consequence, this 10th week will be the last of my Knock Down drawings. It has just turned out that way, I didn’t take the decision rationally. The parametres have changes. Looking for the return is the approaching of a reality, which I would like to explore more now through performative meetings in my “Vienna Coffeehouse” in my Amsterdam studio. I don’t know what will come. Now I need to pause. To write and compare notes. Maybe my work cycles are completely at odds to the movement of a general sigh of relief after this paralysis.

But as mentioned already: To every age its art. To every art, its freedom. I hope that the Sektionsabteilungen, (the Austrian bureaux which run the arts for the state) and which like to claim the credit for the art and culture agenda in Europe, will better incorporate the unexpected and non-traditional work patterns in the creative sector in future, as well as the concerns and needs of the many self-employed, particularly those with children. Children need to be thought of first, so that they don’t miss anything. What are we so afraid of? Did we have enough time to talk to them (kids?) about what is happening? These fabricated urgencies have hidden a lot. Luckily not everything. But these appear to be a general mechanism to prevent us thinking about why we are doing something. That would also be interesting for children to explore. Also for things to become fairer in future. That would be a shimmer of hope. A chance.

***

Presentation of the Artist’s book Mothers Matter at Galerie Ortner2in Vienna, 12.6.2020: Mothers Matter is relevant to all of us. The title has two meanings: a mother’s issue and mothers are important. What is a mother’s issue? The Never come Back Story presents the theme of the book in the first chapter. As the physical transformation leads to a social restructuring, which poses questions about the why and how. Whey should childcare just be a female matter? How is it related to ideals in reality? And how does political language influence the wider understanding of roles in society? Finding a volume, is the title of the second chapter, time to discuss the theme. Not just internally. This book concerns us all. Having Balls and I am not the man I used to be (life as a female artist) show the duplicitous morality of the patriarchal system in which we still live. And the question over who owns the most, a question of financial survival, takes the power to decide away from some couples, as women are still not given equal pay to men. The system manipulates. There is no better time than now for questioning the division of labour in the family according to gender. Through drawing, the art book leads you through the isolation that mothers can feel and looks at how the protagonist takes up her search for a voice in the public and political spheres. Often this search is a lonely exercise but it represents the experience of a large number of women, who find themselves in positions they could never have imagined would happen to them. What life experiences are we passing on to the next generation.

Another drawing of the Knock Down Series you can find at the cover of the latest issue #93/94 of ausreißer – Die Wandzeitung

Barbara Philipp is an artist who works in Amsterdam and Vienna. In her work she explores the ephemeral nature of the physical being and its projections and interpretations in society. Language is an important starting point in her work. Her artistic spectrum spans drawing, painting and performances. She took part in the Mothernists Conferences in Rotterdam (2015) and in Kopenhagen (2017), campaigns for m/other voices and is particularly active in the international feminist exchange of artists with children. She studied at the énsba in Paris, the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna und the Städelschule in Frankfurt.

www.mbassyunlimited.org/008-barbara-philipp/

Foto: (c) Adrian Pasi